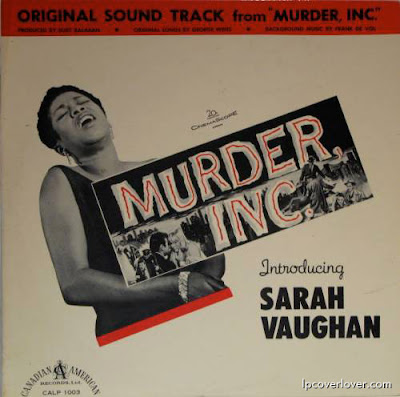

The album cover to the soundtrack for Murder Inc., starring Peter Falk and featuring the screen debut of Sarah Vaughn

The album cover to the soundtrack for Murder Inc., starring Peter Falk and featuring the screen debut of Sarah Vaughn"The bombshell that exploded it all! The hoods! The sleazy babes! The wanton gunmen!"

So announced the trailer for Murder Inc. (you can watch it here), the 1960 movie based on the travails of the notorious mob syndicate. It is the last in Freebird's Dark Harbor film series (co-sponsored by PortSide), chosen by the author Nathan Ward in conjunction with the release of his new history of waterfront crime in the port of New York.

In advance of the screening (Thursday, June 24, 8 pm), the Word on Columbia Street asked us to chat with Nathan about the role our neighborhood played in all of this.

--Peter Miller

In your new book, Dark Harbor, you quote Arthur Miller: "America, I thought, stopped at Columbia Street." Was he referring to our stretch of it? And what did he mean by that comment?

Miller doesn't say precisely which block of Columbia, but it was where in the late 1940s he was shown his first "shape-ups," the cattlecall-like hiring method still prevalent then. I imagine he saw them at several points along the street, since it was the center of so much dock activity then. These visits later served him in writing an unproduced screenplay as well as A View from the Bridge. Of the shape-ups he saw, Miller later wrote of his shock, "their...acceptance of this humiliating procedure struck me as an outrage, even more sinister than the procedure itself." Carlo Levi, the Italian writer banished by Mussolini to Eboli, had titled his memoir of exile, Christ Stopped at Eboli,"which resonated in my head on those cold mornings on Columbia Street. America, I thought, stopped at Columbia Street."

Who was Peter Panto? And what does his disappearance have to do with the film Murder Inc. you are showing at Freebird on Thursday?

Peter Panto was a heroic figure of the Brooklyn waterfront in the late 1930s. He started as a longshoreman, lived at first on State Street, and worked at the Moore-McCormack pier at the foot of Joralemon. Disgusted by the rackets and graft that were a regular part of getting hired, he led a small, growing movement of longshoremen against the union leadership of the Camardas (in Brooklyn) and President Joe Ryan (on the West Side). His speeches against the gangsters' set-up eventually caused him to be called to the President Street office of Emil Camarda, who advised him that "the boys" (i.e., people like Albert Anastasia) did not like what he was up to. Panto defied the warning and was taken for a fatal ride on July 14, 1939. His body was dug up in Jersey more than a year later, after months and months of a graffiti campaign by Red Hook and other longshoremen, who scribbled "Dov'e Panto?" on freight cars and warehouse walls.

The reason I'm showing Murder Inc at Freebird is only because of the brief, heroic appearance of Peter Panto in the story, and because I love Peter Falk, who stars as Abe "Kid Twist" Reles, the most important Mob informant ever, since it was his testimony that not only sent top leaders of the gang to the chair, he also told unsuspecting law enforcement about the existence of Organized Crime in the first place. Brooklyn D.A, Bill O'Dwyer admitted he'd never suspected there was a national crime organization until Abe Reles walked into his offices at the Municipal Building (next to Borough Hall) and started talking. O'Dwyer kept Reles in a suite at the Hotel Bossert on Montague (see picture on right) while he kept on talking, eventually explaining how up to a thousand seemingly random murders across the country had all been planned and executed by what the press came to call Murder Inc. Reles later fell or was pushed from his window under guard in a Coney Island hotel, but he'd done his damage as a witness.

The reason I'm showing Murder Inc at Freebird is only because of the brief, heroic appearance of Peter Panto in the story, and because I love Peter Falk, who stars as Abe "Kid Twist" Reles, the most important Mob informant ever, since it was his testimony that not only sent top leaders of the gang to the chair, he also told unsuspecting law enforcement about the existence of Organized Crime in the first place. Brooklyn D.A, Bill O'Dwyer admitted he'd never suspected there was a national crime organization until Abe Reles walked into his offices at the Municipal Building (next to Borough Hall) and started talking. O'Dwyer kept Reles in a suite at the Hotel Bossert on Montague (see picture on right) while he kept on talking, eventually explaining how up to a thousand seemingly random murders across the country had all been planned and executed by what the press came to call Murder Inc. Reles later fell or was pushed from his window under guard in a Coney Island hotel, but he'd done his damage as a witness.If we were living in this neighborhood in 1948 (when Malcolm Johnson’s newspaper expose about waterfront crime first ran in the New York Sun) what would it have looked like? Who would have lived here?

Well, you have to imagine it before the decline, and picture most of the shops serving the docks in various ways (stores that sold boots and coats, pubs where longies could pass time between shape-ups, law offices, local office, diners like the recently closed Waterfront Diner).

What was the reaction to the expose in waterfront communities like Red Hook? Were only the mob bosses outraged or did it stir up resentment from other working longshoremen?

That's a complicated question. As much as many guys on the docks hated some of the stuff they saw around them on the job, and as much as they resented the various kickbacks, I think at first there was some resentment that the newspapers were exploiting their situation to sell copies, and that there would be no follow-up. Also, don't forget the series appeared in a Republican newspaper that was then anti-labor. The fact that the writer was liberal and a union man himself was not immediately clear. However, Mike Johnson had done a lot of homework for this series, and many of the longshoremen and checkers who wrote him fan letters I think were won over by the extent of his research. The crime series came out the same week in December 1948 that the men went on strike against their own corrupt President, Joe Ryan. He attempted to blame the strike on the newspaper series, but it just didn't work.

You have lived nearby (Brooklyn Heights) for several years now. Did that close proximity to the waterfront play a part in your decision to write this book?

I became intrigued in a sort of atmospheric way by what remained of the old working waterfront in the mid-eighties, when I lived on President Street. But yes, I didn't learn much concretely about it until I moved to Arthur Miller's neighborhood in the nineties.

The films you chose to show this month were all produced in the wake of investigative journalism and crime commissions of the 1940s and 50s. Did this bad press for the neighborhood and other waterfront communities play a role in its clean-up?

You can trace a line from Johnson's crime series in 1948-49 through to the various investigations it inspired:several by the city itself, then the Kefauver hearings, the New york Crime Commission hearings of 1952, through to the establishment of the Waterfront Commission in 1953. I wouldn't say that bad press cleaned things up--as recently as four years ago, Peter Gotti went to prison for, among other things, racketeering on the Brooklyn waterfront. But things became more regularized, the workforce less casual (and thus, a little less exploitable).

Is the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor (located at 100 Columbia Street) the same commission that grew out of the labor racketeering scandals you write about in your book?

Yes, that is the same one, although it's only one of several offices. I was pleased that the new Waterfront Commissioner gave the book a good review. He's the incoming one, brought in after a scandal last year, so he's free to agree with some of the book's darker findings.

What role do they play today in the era of containerization?

The Waterfront Commission is charged with its same job, of trying to keep thugs off the docks, but as my friend Artie Piecoro says with experience, "It's not as though the mob guys wear a sign." Some new tasks the Commission has involve Homeland Security and the threat of a serious bomb smuggled inside a container.

***

Nathan Ward will introduce Murder Inc. and be on hand to sign copies of his new book, Dark Harbor, this Thursday at 8 pm at Freebird Books

No comments:

Post a Comment